Don Yenko knew exactly what he wanted: to become the Carroll

Shelby of the Chevrolet world, to put his name on a car and to have people

instantly recognize it as the leading performance version of that car. And he

did indeed get what he wanted.

Just not with the car he initially intended.

Shortly after Don was born in 1927 in southwestern

Pennsylvania, his father, Frank, started a Durant dealership in 1928, then a

Chevrolet dealership in 1934. The Chevrolet dealership, located in

Bentleyville, Pennsylvania, took off and Frank opened a second in nearby

Canonsburg in 1949.

Don, however, didn't join the family business right away. He

earned his pilot's license at 16, served in the Air Force, then attended Penn

State University for a degree in Business Administration. Only after

graduating, at age 30, did he return to Canonsburg and the dealership and

decide to start racing Corvettes.

By the mid-1960s, however, Corvettes had grown weighty and

the Mustangs and Cobras had gained dominance on the racing circuit. "I got

tired of looking at the rear bumper of Mark Donohue's Mustang," Yenko

famously said. So Yenko took a cue from fellow racer Shelby--using his

connections through the dealership--to create a Chevrolet specifically for road

racing.

Yenko chose as his subject the Corvair Corsa, lighter than

the Corvette by about 500 pounds. According to an article he wrote for the June

1966 issue of Sports Car magazine, Yenko originally designed the aero

body add-ons using cut-up pizza boxes. He didn't get approval to run his

modified Corsa in SCCA until November 1965; significant only because he needed

to build at least 100 such cars by January 1, 1966, to fully qualify the cars

for D Production racing. He got the 100 Corsas from Chevrolet and, along with

his staff at the dealership, converted them all into Yenko Stingers in less

than two weeks.

"The story of the Yenko Stinger tells the story of

Yenko Sportscars," Mark Gillespie wrote in The Yenko Era, his book

collecting various tidbits of Yenko history. "Everything that came later

was tempered in the crucible of the Stinger. What Yenko Sportscars demonstrated

was that a small, close-knit organization, staffed by motivated people and

without the support of a major manufacturer, could succeed."

Yenko himself both raced and sold Stingers, but perhaps more

importantly, he established a nationwide network of dealerships that would sell

the cars (one of which was Nickey Chevrolet in Chicago). The Stinger proved

competitive, and thus the program continued into 1967, but Yenko soon decided

to apply what he learned with the Stinger to the Camaro Z/28 and take it into A

Sedan and Trans-Am racing.

That effort, which he called the Camaro Stormer, fizzled

quickly; Yenko sold just two. He soon tackled another project with a decidedly

different take on the Camaro. Rather than prepare it for road racing, Yenko saw

that Chevrolets, hamstrung by GM's 400-cu.in. limit for intermediates and

compacts, could no longer compete in both stoplight and sanctioned drag racing,

especially when stacked up against the various Hemi-powered Mopars and

427-powered Fords.

Enter Dick Harrell, who had previously worked with Nickey

Chevrolet, and Bill Thomas, who helped Dana Chevrolet in Los Angeles develop

its Camaro 427 conversion. Both Harrell and Thomas showed Yenko how to drop

450hp and 410hp 427-cu.in. big-blocks into the Camaro and create supercars

capable of dipping into the 11s at the dragstrip.

The Yenko Super Camaros took off, assisted by Harrell's

dragstrip campaign in one, and spawned similar 427-powered Chevelles and Novas.

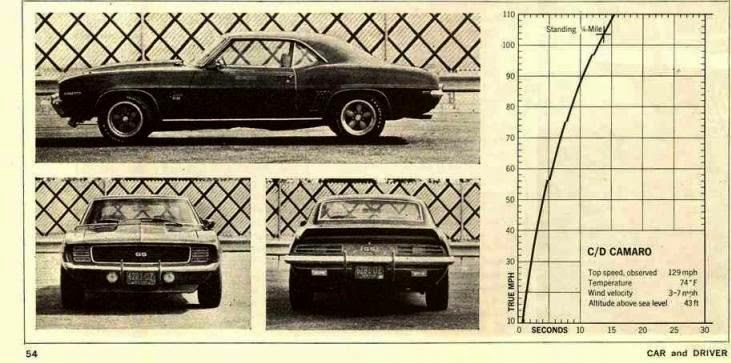

By 1969, Yenko had convinced Chevrolet--via the COPO program--to plant 427s

into Camaros at the factory, saving Yenko the costs associated with the engine

swap. Yet the same bugaboos of rising insurance costs and governmental

oversight that curtailed the factory muscle offerings also put an end to the

Yenko Camaros after 1969.

Yenko made a few attempts to skirt those roadblocks with the

Yenko Deuce, a small-block-powered Nova, and the Yenko Stinger II, a

turbocharged Vega, but the Deuce proved short-lived and the Stinger II's

turbocharged engine ultimately didn't make it past the Environmental Protection

Agency.

All this time, Yenko continued to race Corvettes, either on

his own or as a co-driver with a number of prominent Corvette teams. After the

Yenko Supercars program came to a close, Yenko continued to sell performance

parts through a catalog and through his dealership.

But by 1982, even that came to an end when he sold the

dealership. Five years later, still an avid pilot, Yenko died when he

crash-landed his Cessna near Charleston, West Virginia.

Feature Article from Hemmings Muscle Machines

source: http://www.hemmings.com/mus/stories/2008/06/01/hmn_feature15.html

YOU ARE NOT JUST BUYING PARTS – YOU ARE GETTING OUR CAMARO EXPERTISE

Tags: camaro part, camaro parts, Camaro restoration parts, 69 camaro, 1969 camaro, aftermarket camero parts, chevrolet camaro, ss, z28, rs, chevrolet, restoration, 68 camaro, chevy, 67, 69, f-body, camaro, chevy camaro, chevrolet camaro, gm, z-28, 350, ls1, z/28, pace car, camaro ss, 69 camaro, first generation, copo, fbody, yenko, 67 camaro, 68 camaro, musclecar

http://www.stevescamaroparts.com